“slow boat / calm river / quiet landing”

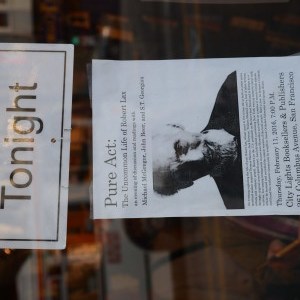

Review of

Pure Act: The Uncommon Life of Robert Lax

By Michael N. McGregor

New York: Fordham University Press, 2015

444 pages / $34.95 cloth

Reviewed by Monica Weis, SSJ

The above words, etched into the gravestone of Robert Lax (1915-2000) capture the life and spirituality of this poet-solitary and friend of Thomas Merton. Michael N. McGregor of Portland State University has presented the literary world with a rich and graceful portrait of a talented and saintly man. Pure Act has already been widely reviewed in the New York Times Sunday Book Review (12/24/15), Publishers Weekly (9/15), America (11/30/15), Commonweal (1/*/16) and The Oregonian (11/4/15), to name a few. From them we learn that McGregor’s personal memoir passages are “vivid and engaging,” that this is a “warm, sympathetic literary biography of this complicated man who lived life as simply as possible,” and that Lax’s poetic subjects were both “visionary and ordinary, celebrating the apocalypse of the everyday.”

But it is Lax’s relationship with Thomas Merton that is of primary interest to the present audience, and Pure Act offers us keen insight into their meeting at Columbia University (1935) as well as the depth of their friendship evidenced in thirty years of correspondence and six visits. For sure, they were a salutary influence on each other despite notable temperamental differences. As McGregor perceptively notes, “Merton was a brilliant and tireless self-promoter, while Lax was often taciturn or tongue-tied in public . . . Merton was vitally concerned – in college and later – with finding answers, while Lax seemed much more comfortable with questions” (32). Yet both of them were not searching, as McGregor rightly distinguishes, but “pursuing . . . a sense of truth and of God and of themselves free from the expectations and trappings of the culture surrounding them” (78; emphasis added). Merton, for his part, discovered Roman Catholicism and his vocation as a writer and Trappist monk. Lax, a later convert to Roman Catholicism, remained a lifetime reader of Hebrew scripture and had, perhaps, the greater struggle and longer spiritual journey.

Bereft after Merton entered the monastery at Gethsemani in December 1941, Lax felt drawn to be with the poor in Harlem. In dire need of psychological healing and a philosophy of solitude – the dark aspect of Lax’s life that James Harford could not develop fully in his 2006 Merton and Friends: A Joint Biography of Thomas Merton, Robert Lax, and Edward Rice – Lax worked for a time in a menial job at The New Yorker which he considered a “toxic” environment. His unrest persisted because he could not write on command, preferring instead sudden inspirations he called “trumpet attacks” (103). He briefly tried his hand at teaching at the University of North Carolina, Connecticut College and a state college in South Dakota, and for a short period also wrote scripts for the Hollywood film industry; he traveled back and forth between Europe and New York City, worked as an editor for New-Story, was a roving reporter in Greece and Europe for Ed Rice’s Jubilee, and much later annually visited Paris and his publishers in Switzerland. In his early years, he seemed unable to settle in one place for very long, always needing a job and money to subsist, yet never abandoning his commitment to writing and reflection. By age thirty-five, notes McGregor, Lax willingly embraced poverty and a life of quiet, moving between Rome, Paris and Marseille, committed to his vocation of writing “that spoke of the beauty of God’s world. God’s people. And he could show those around him what harmony, grounded in love, looked like” (159-60).

From several comprehensive chapters we learn that Lax’s poetry gained a wider audience when Emil Antonucci, working as a graphic designer for Jubilee, began releasing hand-press versions of his poems (204). (It was Antonucci who illustrated Merton’s Original Child Bomb for PAX, a short-lived attempt by Lax to publish poems and art that would promote peace.) Throughout Europe Lax was seen as a forerunner of the concrete poetry movement, although he preferred to be regarded as a minimalist. The Merton-Lax connection was in the spotlight again with the 1978 publication of A Catch of Anti-Letters and a 1980 conference on Merton and Jacques Maritain in Louisville. For some unexplained reason, Lax’s talk, “Harpo’s Progress: Notes toward an Understanding of Merton’s Ways” was not given but later published in the inaugural volume of The Merton Annual (1988). Lax was again in the public eye in the 1984 PBS documentary Merton: A Film Biography, in Michael Mott’s The Seven Mountains of Thomas Merton, and in his invited review of the first volume of Merton’s correspondence, The Hidden Ground of Love, for St. Bonaventure’s literary journal Cithara. McGregor’s research unearths not only these connections, but also the complexity of Lax’s publishing history, his invitations for readings, a major exhibit of his work in Stuttgart, and his growing reputation in Europe. We experience his personal and literary struggles and triumphs. Quoting Stephen Bann’s critique of Lax’s poetry, McGregor offers two reasons why Lax’s poetry matters: he is countering the “overly secular approach to poetry” then popular and making “momentous statements about human existence in our times” (289).

Peak moments for this reader are the links between Merton, Lax, Mark Van Doren, and Bramachari, and the pull of the Olean roots which offered Lax the balance to his “attraction to urban energy and rural peace” (51). Also engaging is the extensive attention paid to Lax’s deep friendship with the Cristiani family whose circus act he followed through western Canada in 1949. This early relationship with acrobats who knew how to concentrate on the present moment inspired Lax’s poem-cycle The Circus of the Sun (thought by some to be the best writing of the twentieth century) and Mogador’s Book (1992) published almost fifty years after meeting Paul (Mogador) Cristiani. Lax was fascinated, too, by Limnina, the rug weaver on the Greek island of Kalymnos and the local fishermen/sponge divers who persisted in their age-old, dangerous practice of sinking deep into murky waters to retrieve their catch. Each – the acrobats, the rug weaver, the sponge divers – presented Lax with a contemporary expression of Thomas Aquinas’ notion of God as pure act: “when we act consciously and yet spontaneously, . . . we become pure act ourselves – we become like God. If, that is, we act in love” (25).

Lax’s extended years on Kalymnos offered him the physical and psychic space he longed for, and he often sent poems and journal entries to Mark Van Doren, whom he considered his ideal reader (273). Sadly, by 1967, his Columbia friends were dying (Ad Reinhardt, Bob Gerdy, John Slate), and also his brother-in-law Benji Marcus, followed in 1968 by the death of Seymour Freedgood and Lax’s soul-mate Thomas Merton. Lax and Merton had spent six days together the previous June with Lax planning to return to Greece and Merton to travel to Asia. McGregor remarks that after so many deaths, “the tenderness and concern between them must have been palpable” (291). Now Lax was more alone than ever. By 1972 he was shuttling between Kalymnos, Lipsi and Patmos, his three favorite islands, mourning the death of Van Doren, his primary audience, reading in the mornings, journaling in the afternoons and talking to the locals – reminiscent of what Thoreau called his “morning work” – a balance of wakefulness and work. Greek life, Lax said, taught him how to pray (314).

Lax’s journey to New York State’s Art Park for a month-long residency two days before the 1973 political coup on Cyprus, however, reinforced the islanders’ suspicion that this gentle man who chatted with everyone and took notes on all he was seeing was in reality a spy. His eventual return to the island two years later did not completely reinstate their trust; consequently, at age sixty-six, Lax settled on Patmos for the last years of his life – when fortuitously he met Michael McGregor. Only when his health declined in 2000 was Lax persuaded by family to return to his home in Olean where he died on September 26, no doubt surrounded by memories of the late 1930s when Lax, Merton and Ed Rice spent summers there as “literary bohemians” in their “Himalayan kindergarten” (80-81) reading Joyce’s Finnegans Wake and writing their own novels.

Presenting Lax as an embodiment of the “wisdom of simplicity” (11) and himself as a “naïve boy who had washed up on his shores” (13), McGregor becomes both unobtrusive character and reliable narrator in this text, connected to Lax by the author’s own need for personal searching. McGregor’s fifteen-year acquaintance with Lax, his voluminous research, and six years of constructing the twenty-six chapters of Pure Act entitles him to offer credible insight into the trajectory of Lax’s life. This is a readable biography interspersed with snippets of poetry, and pertinent passages from Lax’s journals. The text follows a loose chronological order, with chapters focusing on themes, then looping back to Lax’s life pilgrimage where, says McGregor, Lax had finally found “his own way of walking. His own way of singing the song. His own way of being pure act” (393).

I strongly recommend reading (and enjoying) this book, especially before the June 15-18, 2017 Fifteenth General Meeting of the International Thomas Merton Society at St. Bonaventure University, when participants will be able to visit the Lax family cottage as well as to steep themselves in a special exhibit of Lax’s poetry and journals curated by Paul J. Spaeth, Director of the Library and Curator of the Lax Archives.

Monica Weis, SSJ received the ** “Louie” award for service to the International Thomas Merton Society. Emeritus Professor of English at Nazareth College, Rochester, NY, she is the author of Thomas Merton’s Gethsemani: Landscapes of Paradise (2005) and of The Environmental Vision of Thomas Merton (2011); her new book on Merton and Celtic spirituality will be published later in 2016.